Vocation of the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur: Education

“It is true that not only the educational links have been broken but education has become too selective and elitist. It seems that only people or persons who have a certain level or who have a certain capacity have a right to education, but certainly all children and all young people have a right to education. This is a global reality that makes us ashamed. It is a reality that leads us to a human selectivity, and that instead of bringing peoples closer, it distances them; it also distances the rich from the poor; it distances one culture from another … And here comes our work: to find new ways.”

Pope Francis, World Congress on Education, Rome, November 21, 2015

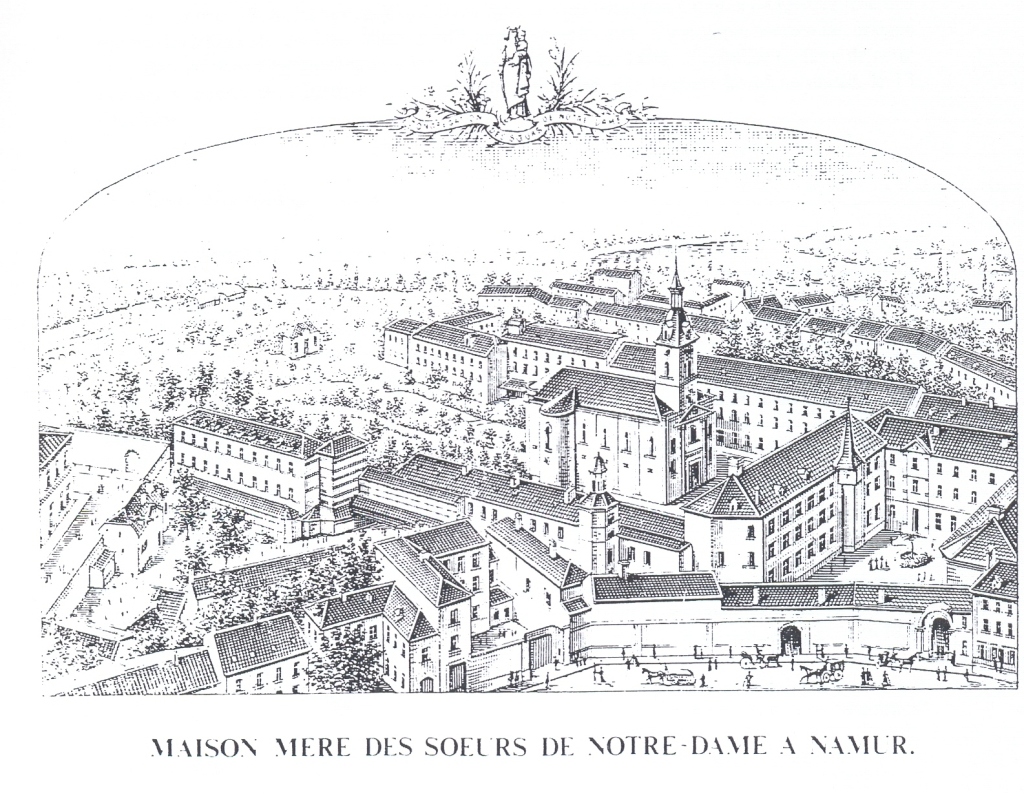

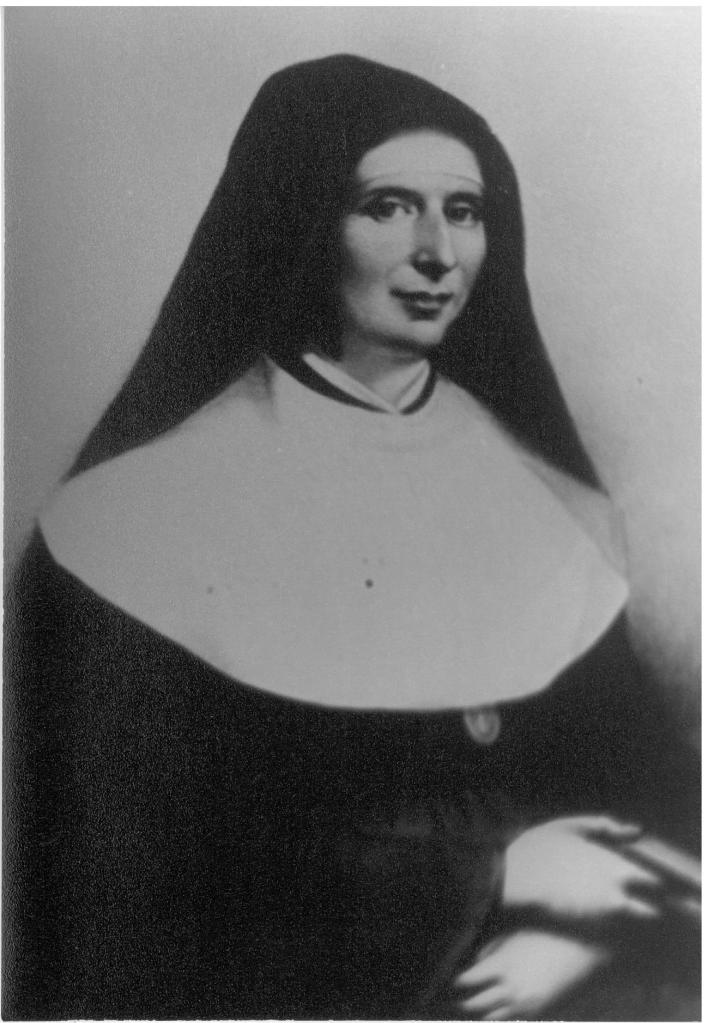

The tradition of the Congregation of the Sisters of Notre Dame is centered on education. This latter is marked by the gospel values lived by Saint Julie Billiart, such as goodness, trust, respect for human dignity and for that of the Son of God.

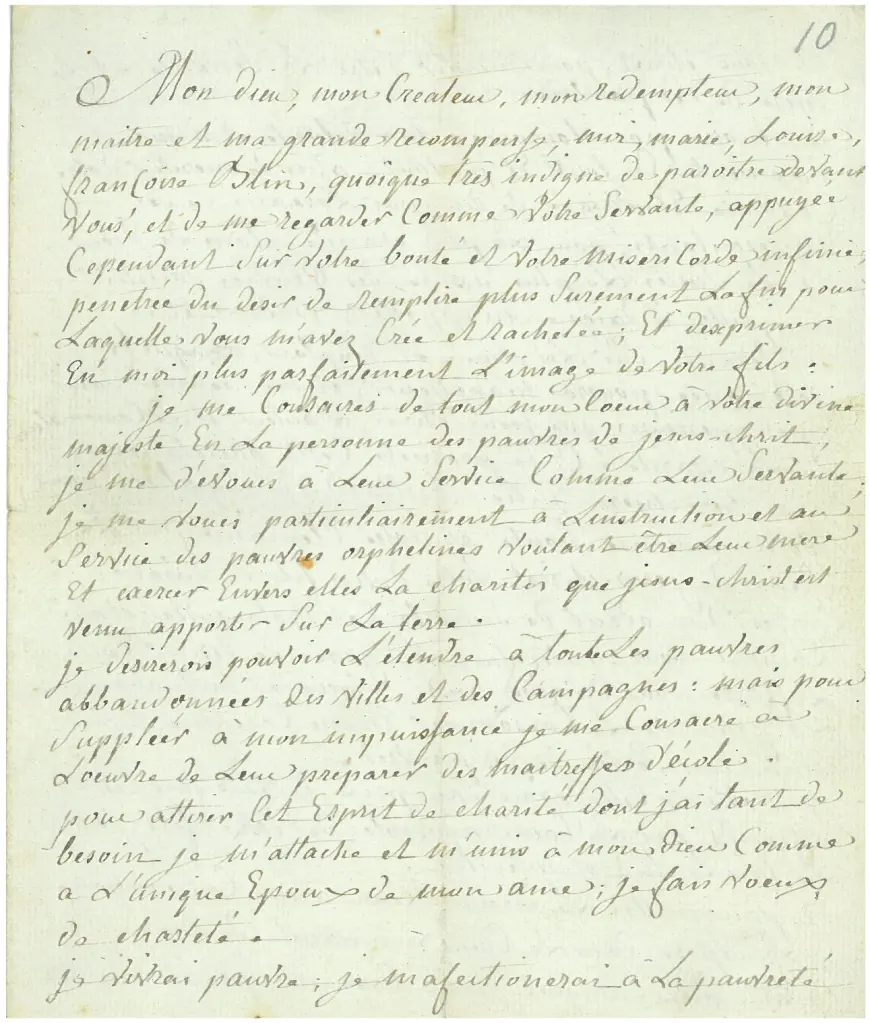

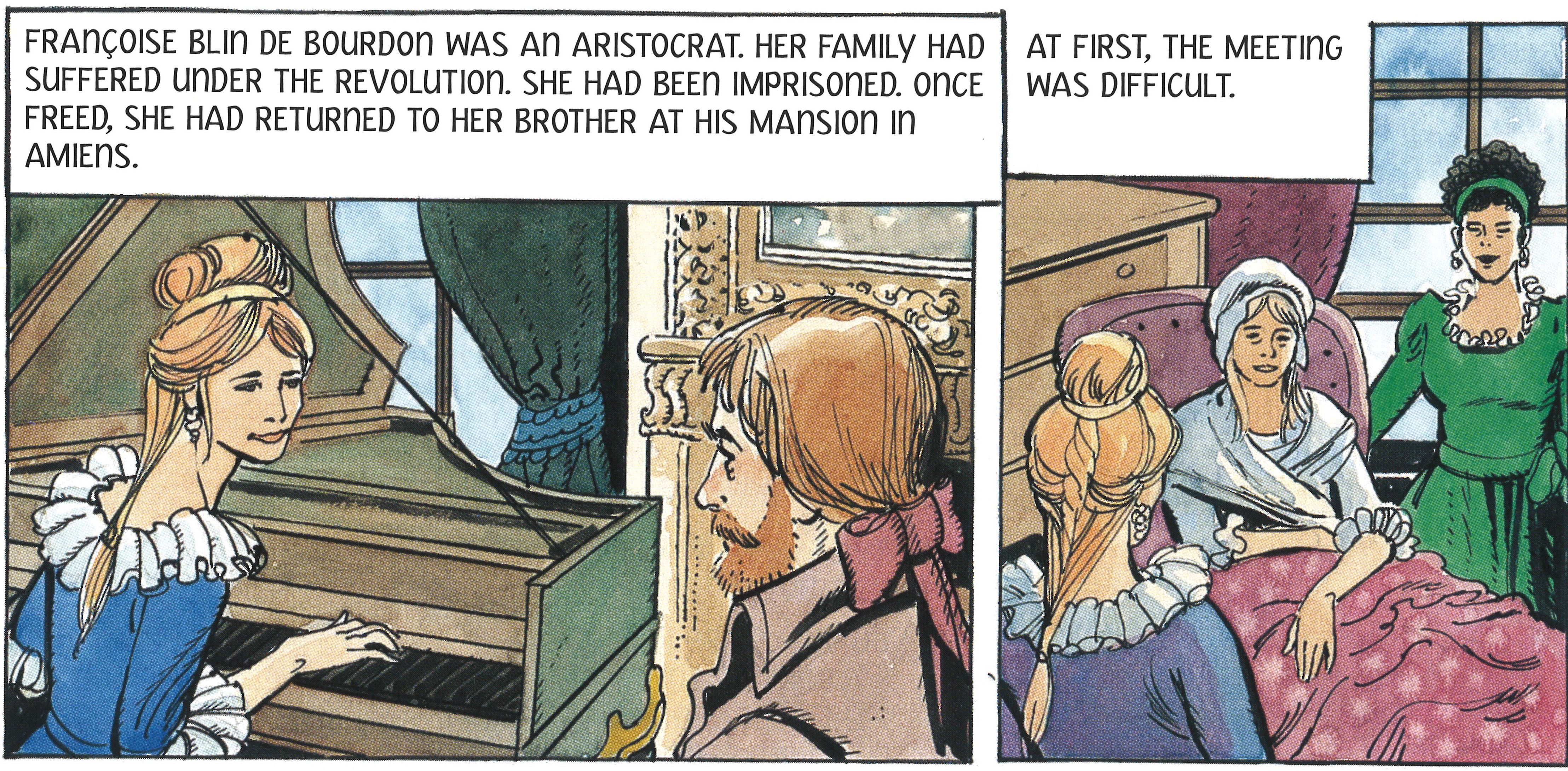

On February 2, 1804, Julie Billiart and Françoise Blin de Bourdon consecrated themselves to God by means of the vows of chastity and poverty and they founded an institute dedicated to Christian education. The act of consecration of Françoise Blin de Bourdon is preserved in the General Archives of the Congregation. Here is what can be read related to the mission to which she gives herself: Françoise commits herself to work with all her strength for the religious instruction of “poor orphan girls”. To “compensate for her own inability to extend her service to all the abandoned poor of the towns and countryside” she proposes to “prepare school teachers” who would go wherever they might be needed.

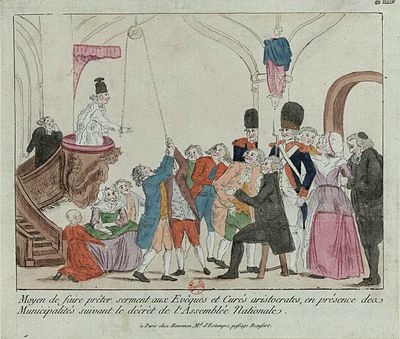

The historical climate and the beginnings of the work of education

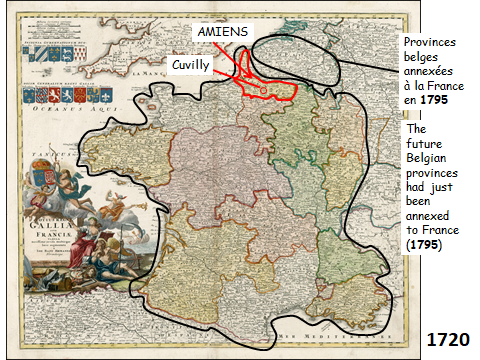

We are in the days following the French Revolution of 1789. Yes, the National Convention put forth the idea of schools accessible to all children and, moreover, drafted school legislation that was a source of hope but that did not produce significant results. Not one primary school was opened. The children whose families are able to pay fees are instructed by teachers who lived on this remuneration. To combat the lack of education on the part of the poor, the Church created a few Sunday schools but no free classes were available on a daily basis. The children of the poor grew up, therefore, in the most complete ignorance. “Providence placed Julie in the place and at the moment where her life could be the most fruitful. Fifty years earlier, her work would have been impossible; fifty years later, it would have been too late.” (Sister Mary Linscott, To Heaven on Foot, 1969.)

By consecrating her institute to the education of the most poor, Julie is filling an institutional void. That is why, at the creation of her first classes, Julie only wants poor girls who are not able to pay for their instruction.

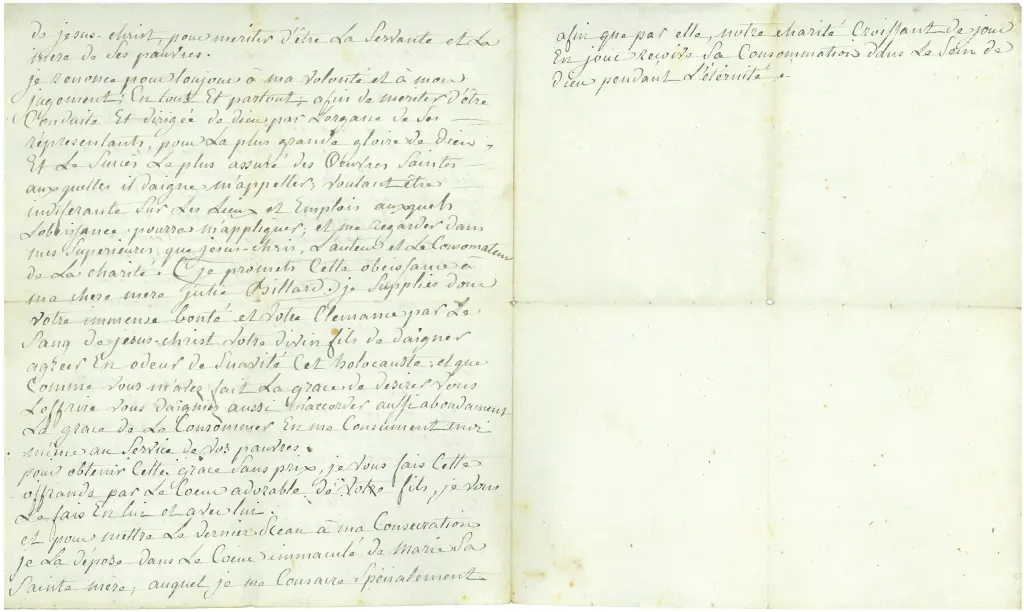

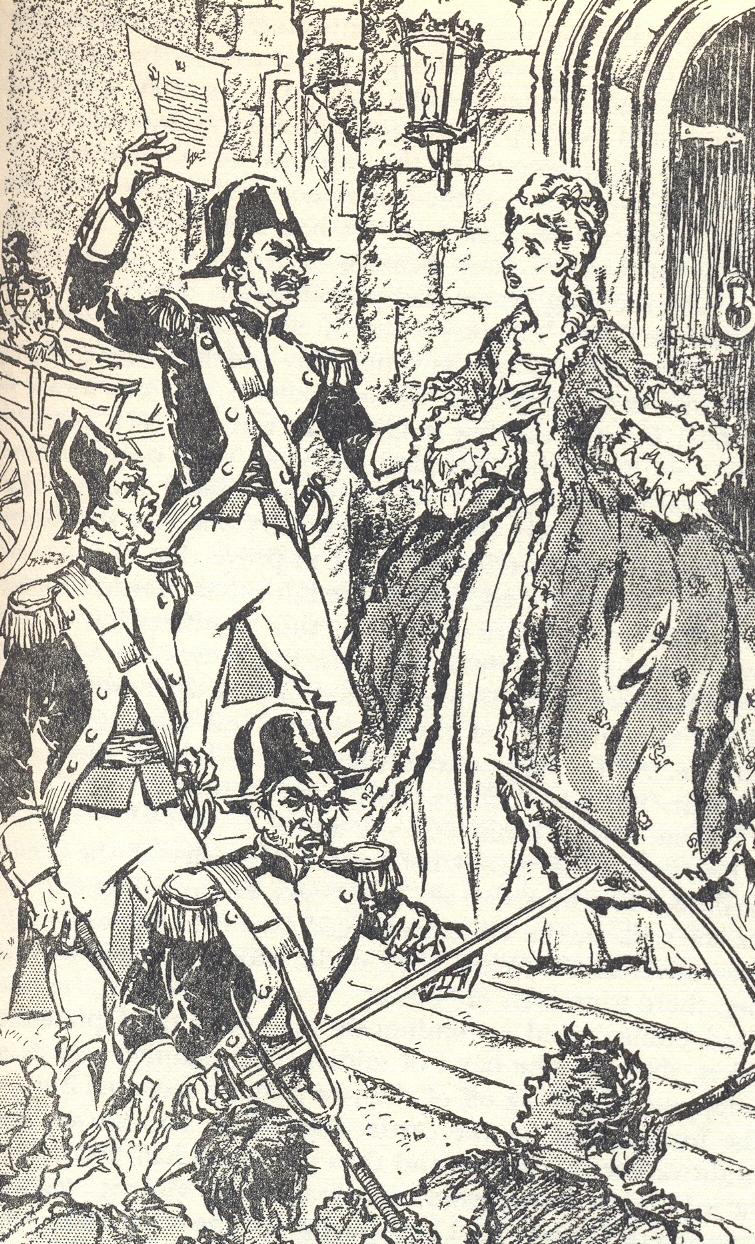

Napoleon’s power does not make the life of teaching congregations, or of those who ran hospitals, easy. He capitulates, however, realizing that education was too costly for the state and he authorizes congregations to do it. An imperial authorization is required, a recognition not given by virtue of the right of freedom of association but incumbent upon services rendered regarding teaching or assistance.

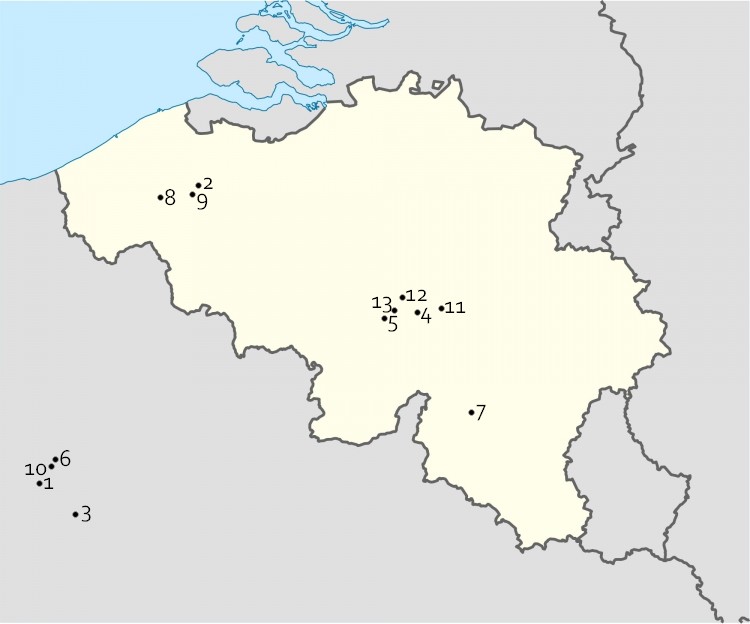

On June 19, 1806, the statutes of the Association called Notre Dame are approved by Napoleon. The opening of free schools is authorized. The first classes of the Sisters of Notre Dame open in Amiens in 1806.

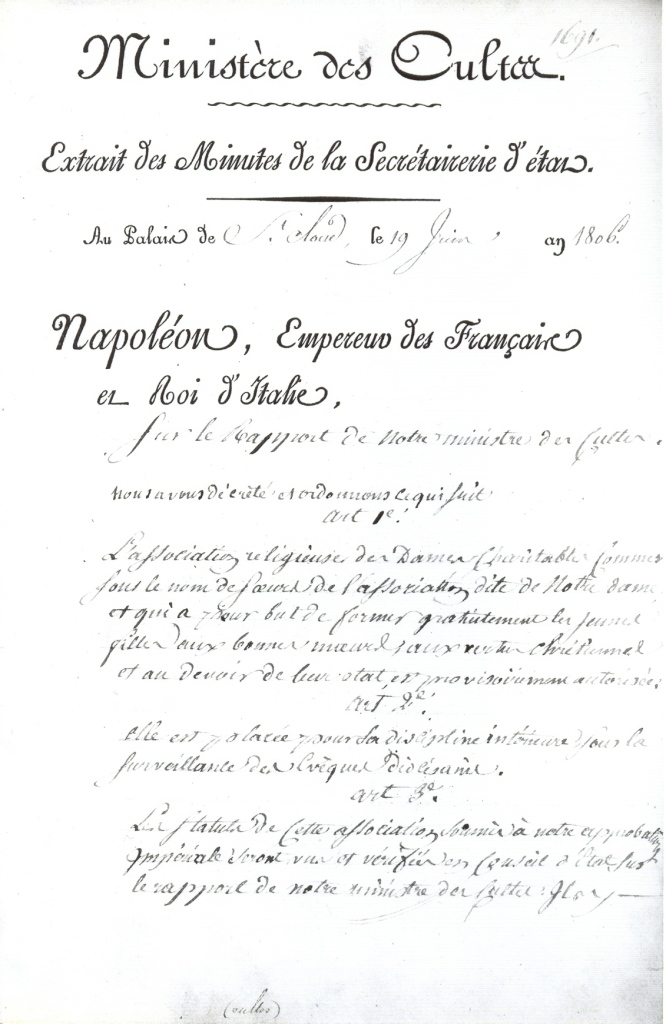

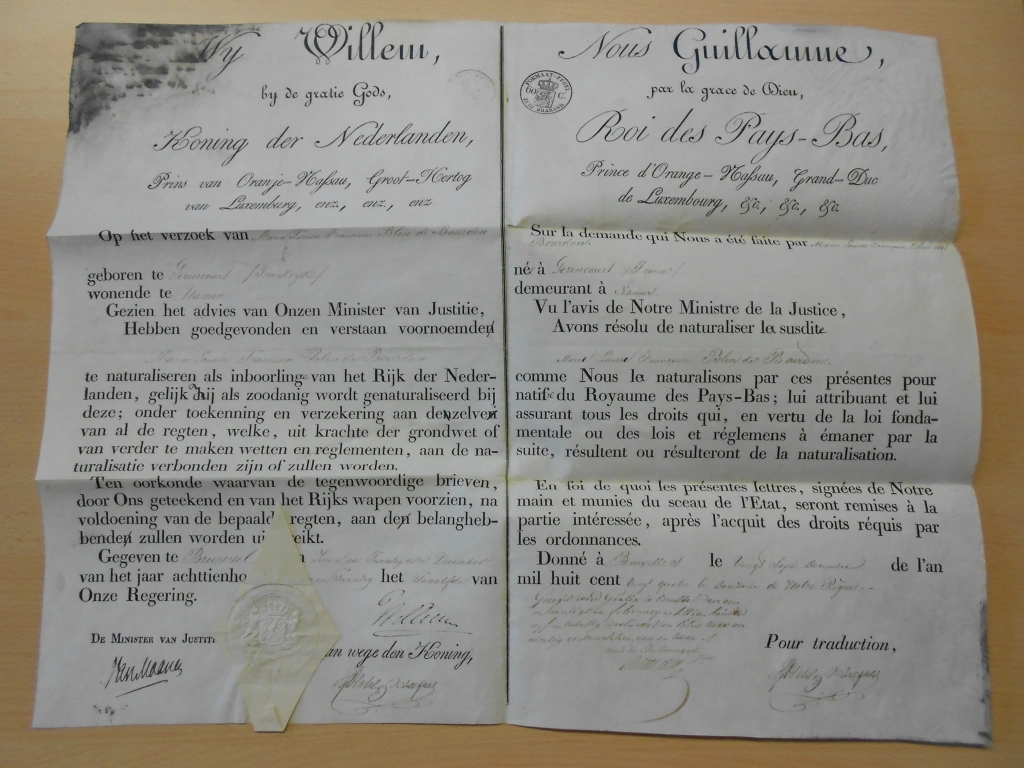

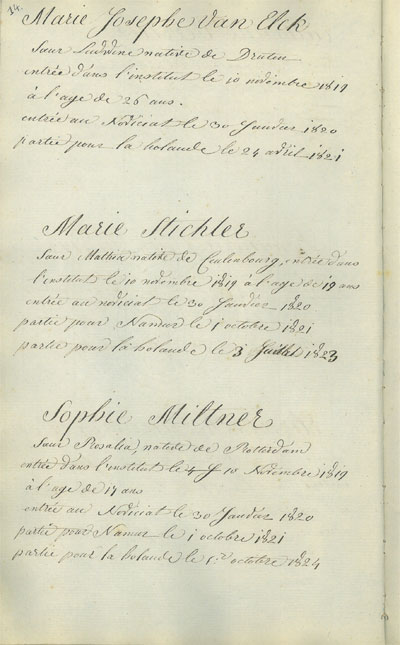

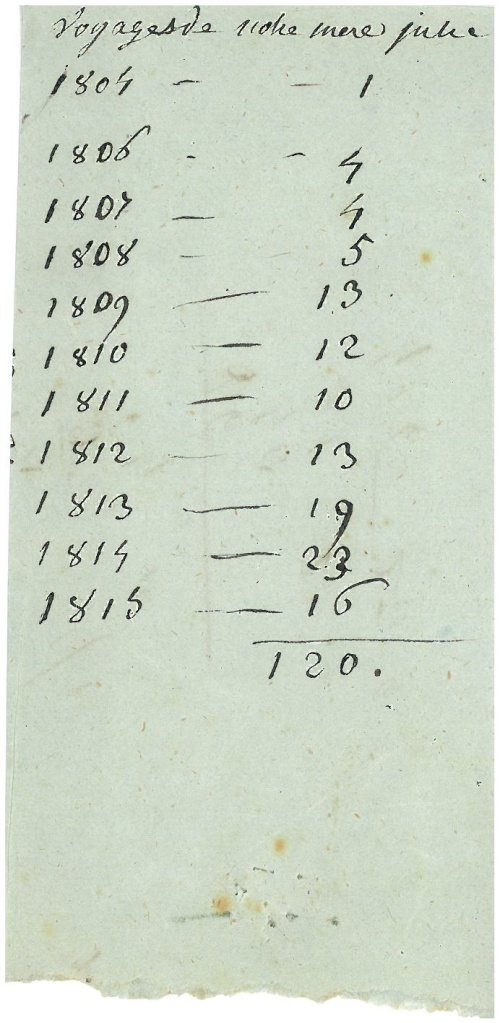

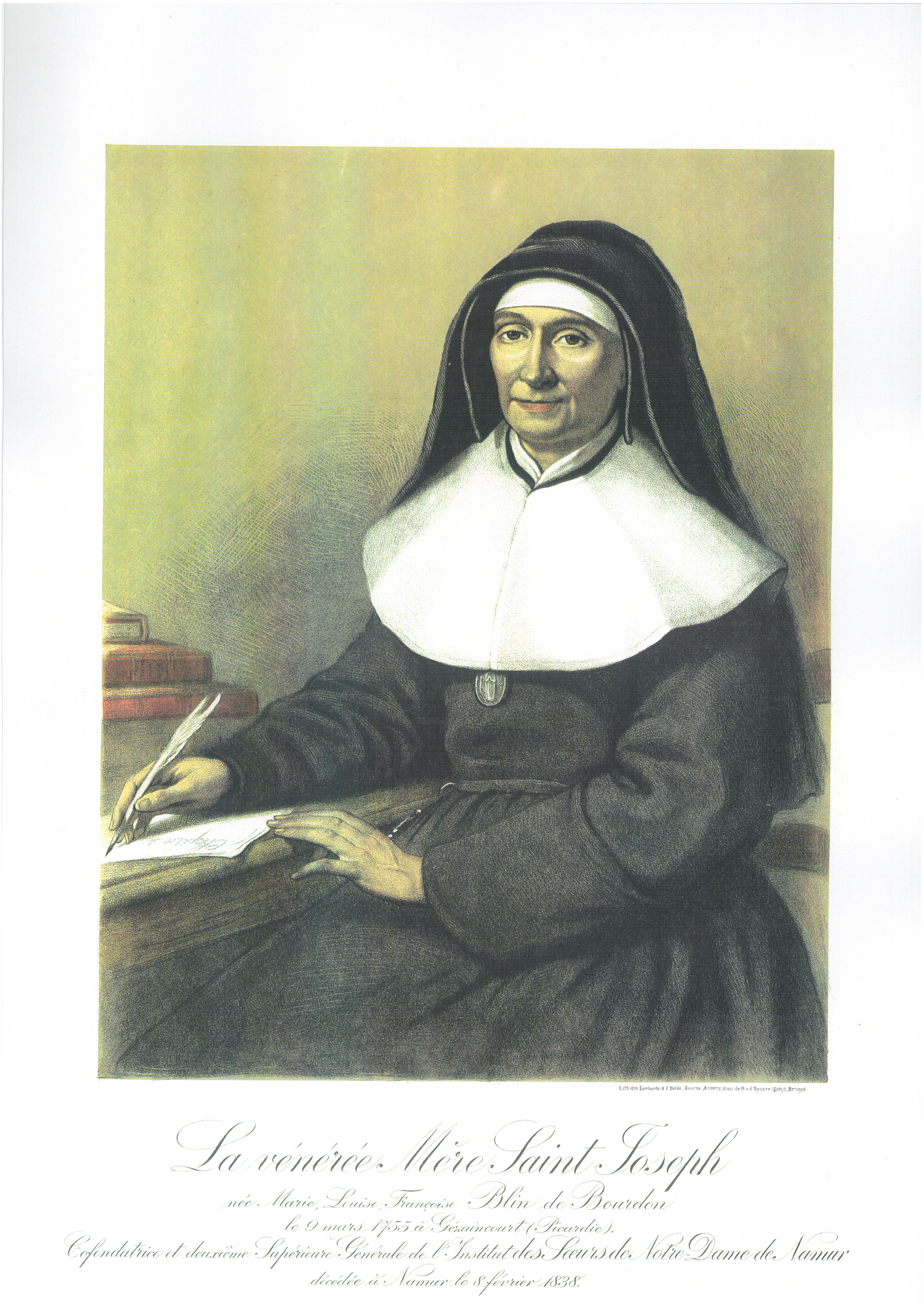

Upon the death of Julie Billiart in 1816, around ten schools exist. Mother St. Joseph opens others, but between 1815 and 1830, the Dutch government of William I imposes major impediments on Catholic education. The King’s project is to laicize education and to refuse any foreigners the right to exercise authority over instruction. King William I sets the number of sisters authorized to live in each house. The Sisters are obliged to take an examination before a committee of instruction. Mother St. Joseph thinks about resigning as Superior General in favor of a Sister of Flemish origin for the good of the Congregation. In the meantime, Mother St. Joseph had accepted taking charge of several nursing homes since schools were no longer viable. Finally, in December of 1824, she receives her document of naturalization and becomes a citizen of the Netherlands.

Education: qualified religious for an effective mission

- A good formation

Given the demands of the profession, the candidate must possess the required qualities, among which are a sincere Christian faith and the ability to share it, to communicate it with warmth and joy but also with firmness. “Persons of a cheerful character are chosen to form children…” (Julie, Letter 349, September 1, 1814). “It must not be said of an educator that she is too kind. We live in a century when so much strength of soul, so much character is needed!” (Julie, Letter 168, March 16, 1811).For Julie, character development and the personality of the teachers was of primordial importance. “What the teacher is has more importance than what she does or what she knows.”

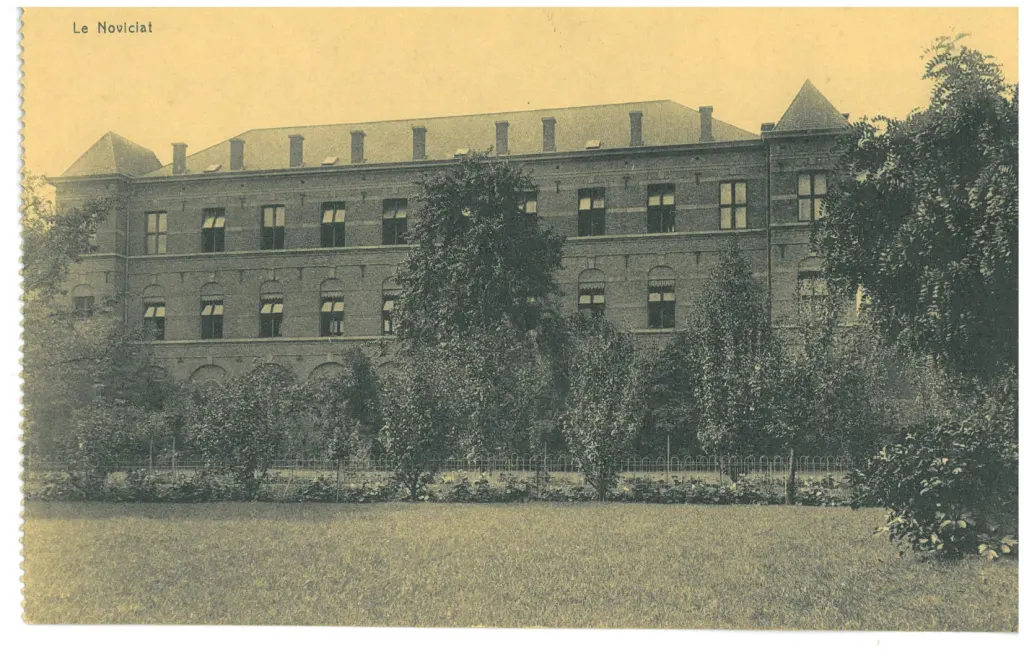

The period of formation (the novitiate) lasts two years and provides the sisters with a basic formation. As Mother St. Joseph underscores: “The novitiate is rather long. Since they are in large part destined to teach, they must be well formed in religion and in the sciences; a few years are necessary even if some still come from good families, already well instructed, and if some of our students are destined for our state of life, which shortens the task” (Mother St. Joseph’s letter to her family, January 1832). The Sisters are then sent to secondary houses sometimes far from the Mother House. The experience that they will acquire will continue to form them throughout their life.

2. Curriculum building

In order to establish schools, Julie Billiart needs teachers sufficiently instructed and capable of undertaking the education of children. Julie applies herself first to this work of formation to which she attaches great importance. It is she who takes charge of the instruction for which she possesses competency. The novices take classes given by Julie Billiart herself. She describes in her letters the method that she is using: “…all the sisters learn their catechism by heart; I make them repeat it , and then the sisters ask one another the questions. After that comes the explanation of the articles. I can see that it is going well.” (Letter 64, January 19, 1808). The influence of Julie Billiart lasts beyond her death because her texts or the examples that come from her life are used for these pedagogical ends or for purposes of edification.

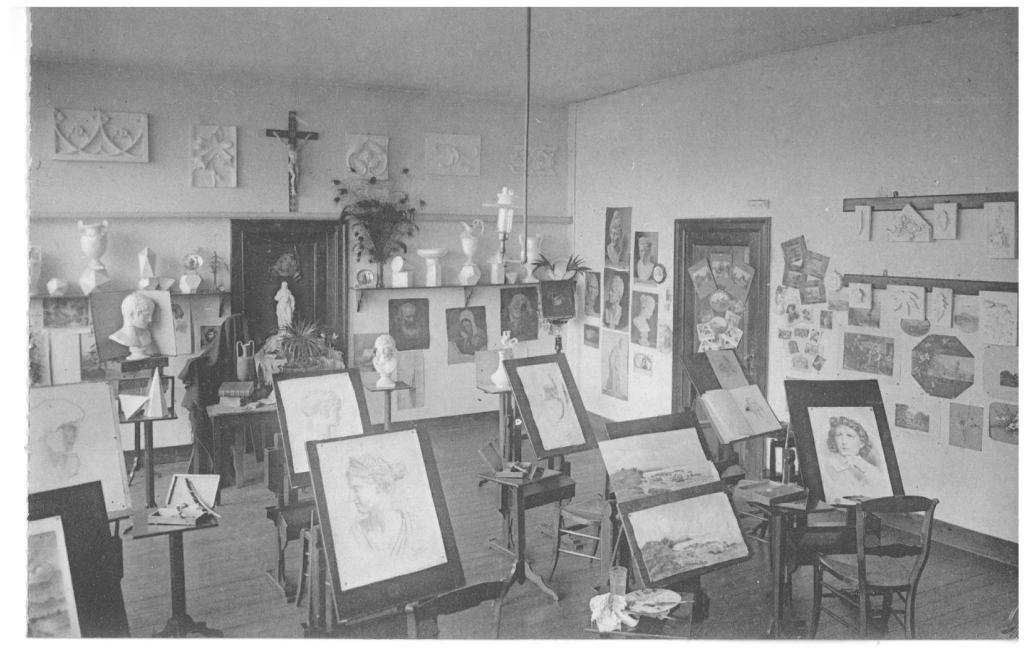

The formation included at the same time both religious and profanes branches. “We must always put the exercise of religion first in obligation, before writing and counting, etc. We must do the one and, as much as possible, not neglect the other.” (Julie Billiart, Letter 162, November 24, 1810). Although prioritized, the two competencies are envisaged from the time of the novitiate. Writing is very important. The sisters also receive a formation in language. The first religious also receive the assistance of the Fathers of the Faith with respect to their formation in the sciences. The course in arithmetic was occasionally given by Father Thomas, a former professor at the Sorbonne. “All that I ask the good God is that you may be occupied in improving your minds as much as possible.” (Julie Billiart, Letter 296, December 24, 1813).

It is essential that the teachers know more than their pupils. Lack of competence on the part of teachers can become the cause of the withdrawal of boarders and the importance of paying students for the good functioning of the Institute is known. “It is a duty for us ‘not to spare either care or effort in becoming well educated. It would be a great disadvantage for the education of our children to proceed too quickly.” (Julie, Instructions)

3. A pedagogical formation

In addition to this knowledge, the novices receive a pedagogical formation. Normal schools (for teacher training) did not exist until the beginning of the 19th century. Julie Billiart developed a true methodology of teaching. If order and discipline were indispensable conditions for instructing children, Julie insists very much on the love of and respect for children. “Take care also to be very gentle with the children.” (Letter 57, August 31, 1807) “Be especially careful about speaking with respect to your children if you want them to respect you and love you.” (Letter 335, June 28, 1814) Julie, herself, loved children “with a supernatural love, intelligent, and as tender as profound”: “I embrace all my little girls, whom I love very much.” (Letter 126, June 17, 1809) “I am distressed at not seeing them.” (Letter 144, March 14, 1810) “How pleased I shall be to find progress since my departure! Write and tell me if they are very good.” (Letter 150, June 8, 1810) The progress of the children is followed regularly by the Superior General who asks to look at their notebooks. The religious teachers keep up to date on changes that are proposed in educational matters, whether to support them (in music, for example) or reject them.

The students

The teaching apostolate of the Sisters of Notre Dame has for its objective the education of girls in Christianity as well as to teach them disciplines that permit them to take an active role in society. “Our institute only proports “to form, by means of education, Christian mothers, Christian families” (Julie, 23nd Conference). Julie insists on respect for the dignity and the sacred nature of each student. She wants schools where each student might become fully herself. “Take a large view of all that belongs to religion but not with a view to forming ‘little devotees’ but good Christians, persons useful to society, great souls capable of persevering in the good.” (Julie, Letter 79, July 6, 1808)

- The different categories of students

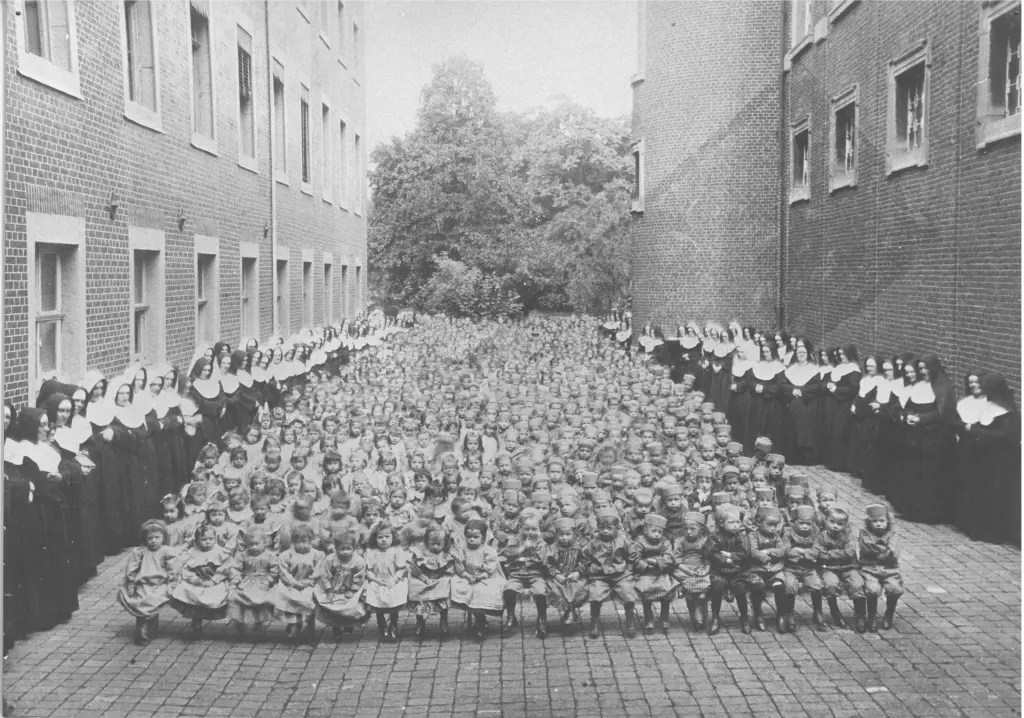

The first sisters of the Institute welcomed into their classes girls younger than 16 years of age (Julie Billiart, Letter 222, October, 1812). These children are separated into three different groups based on family means (poor students, paying day students and boarders). It is very clear that the class of poor children is the principal focus at the origins of the Congregation.

In her research, Cécile Dupont gives us information on these students.

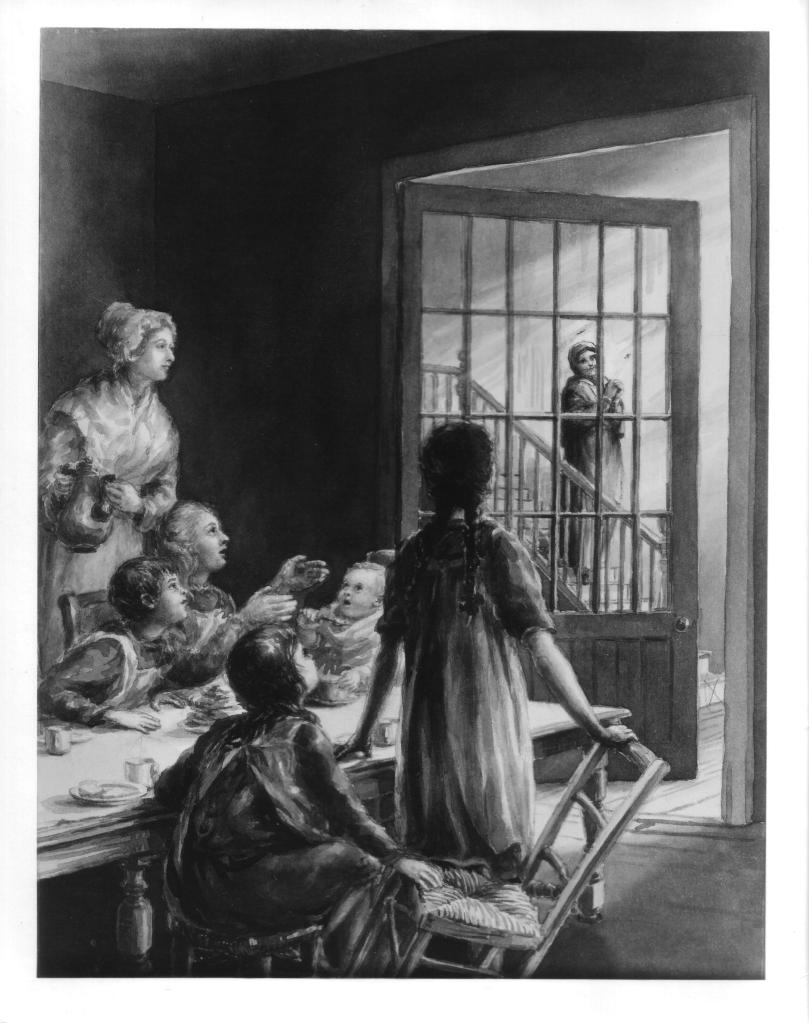

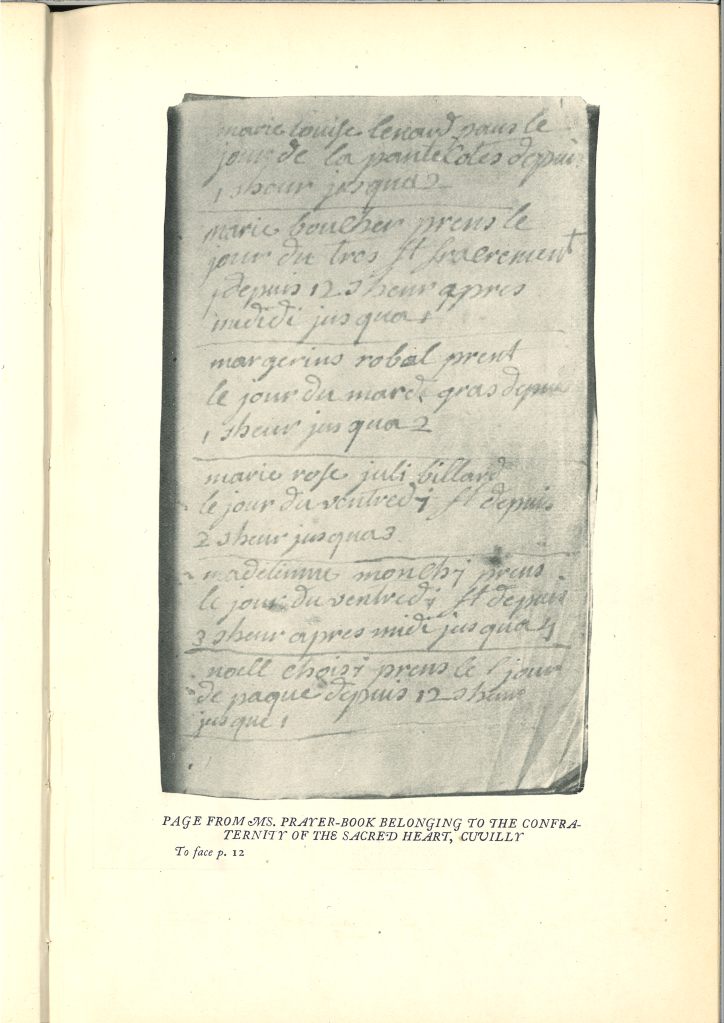

“At the beginnings of the Institute, Julie’s main attention turns toward the poor: “We exist only for the poor, for the poor, absolutely only for the poor.” (Julie, Letter 86, end of November, 1808). The main concern of the first sisters is to foster them, to have them return to class. The children are numerous but not necessarily diligent. One class counted close to 100 pupils; a teacher speaks of: “troupes of poor little children from desperate circumstances as much for physical needs as for their souls.” (Letter from Catherine Daullée, January 2, 1809) These poor children belonged primarily to the working class. Before tackling the needs of the soul, the sisters tend to the body. In front of these bodies “…dirty, eaten by lice, filled with scabs, with ringworms, without blouses, without stockings …whose body can be seen bare from all sides…” (Letter from Catherine Daullée, January 19, 1811). The sisters distribute blouses, bonnets, handkerchiefs and other clothing. These articles of clothing are a manner of publicizing the work of the Congregation but they are especially a way of causing poor children to return. These gifts are accompanied by meals offered to the indigent children and sometimes gifts of money (Letter from Catherine Daullée, April 11, 1811). “This is the disadvantage that exists in this country. If the children are not dressed, they do not stay in the classes” (Letter from Catherine Daullée, January 19, 1811. Françoise Blin de Bourdon conveys in her letters some of the most practical aspects. The classes are given during her mandate as superior from 8:00 – 11:30 am then from 1:00 to 5:00 pm. In some towns, however, there is the issue of children who arrive very early at the convent, among other things, to be fed there. When the body is full and more presentable, lessons are able to proceed more effectively. The schedule of the classes for the poor consist in studying religious principles, reading, writing and the basics of mathematics. Practical competencies are taught, as well, to the poor students. In Ghent, they practice lace-making. However, the catechism remains the focus of their education.

Boarders are less numerous. From the first days of the Institute, there are often fewer than 10. Attracting them becomes a question of survival because they are the principal source of revenue in the secondary houses. Boarders wear a uniform. Julie Billiart hopes in this way to combat coquetry and promote simplicity. (Testimonies of contemporaries, Mother St. Joseph and education at the boarding school in Namur, 1816-1838).

The boarders receive an education in their language as far as possible (Flemish principally) and learn French. Religion is also taught in the boarding school because the children of the leisure class must practice Christian virtues and, in particular, charity. The other subjects taught are the same as in the poor classes to which are added the sciences and the arts in more depth (astrology, bookkeeping, music, drawing…) The curriculum is expanded as instruction evolves. Mother St. Joseph puts forth the fact that it is necessary to stay up to date with what is happening in the other Orders so as to “respond to the needs of the times” (Testimony of Félicité Minez, Mother St. Joseph and education at the boarding school in Namur, 1816-1838).

Some other students, paying day students, are welcomed into the schools of the Institute. Their curriculum is less broad than that of the boarders. They do not take music and drawing. The classes are generally of medium size, fewer than 100 students.

A last category of students is mentioned occasionally in the letters of the Superiors General: the neophytes, older girls whom the parish priest wanted to rescue from unfavorable moral conditions by having them live at the convent and who compensate for the burden they represent by making lace. (Julie Billiart, Letter 189, October 19, 1811.

2. Curriculum and methodology

The first courses of study are simple and only slightly differentiated for the paying students or the free classes. The interest brought to methodology and to the pertinence of a “new program of studies” is developed after 1830 (Annals of the General Archives, volume 3, May 3, 1833). Circumstances become more propitious for reflection on method and curriculum. In 1832, Françoise Blin de Bourdon, in collaboration with the Jesuits, established a broader curriculum. The annalist of the sisters explains: “Under the direction of Reverend Father Méganck and other Jesuit Fathers, our principal sister teachers are going to be occupied with drawing up a plan of studies more extensive and more appropriate to the needs of today.” (Annals of the General Archives, volume 3, August, 1832.)

Methodology had already undergone significant modification by means of the adoption of that coming from the Christian Brothers (Congregation founded by Jean-Baptiste de la Salle (1651-1719) for the purpose of forming free schools for poor boys.) The sisters use signals to direct the children. Those of Julie Billiart and Françoise Blin de Bourdon, little instruments of wood or metal and producing a dry sound or click, are preserved in the Heritage Center established in the heart of the Mother House.

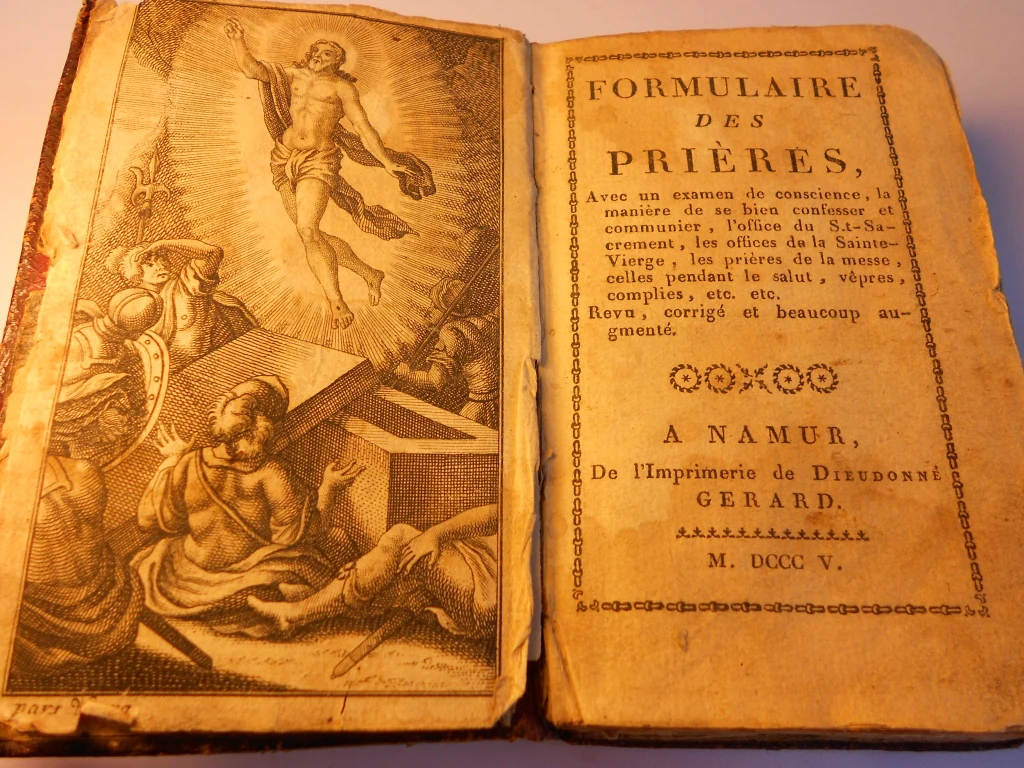

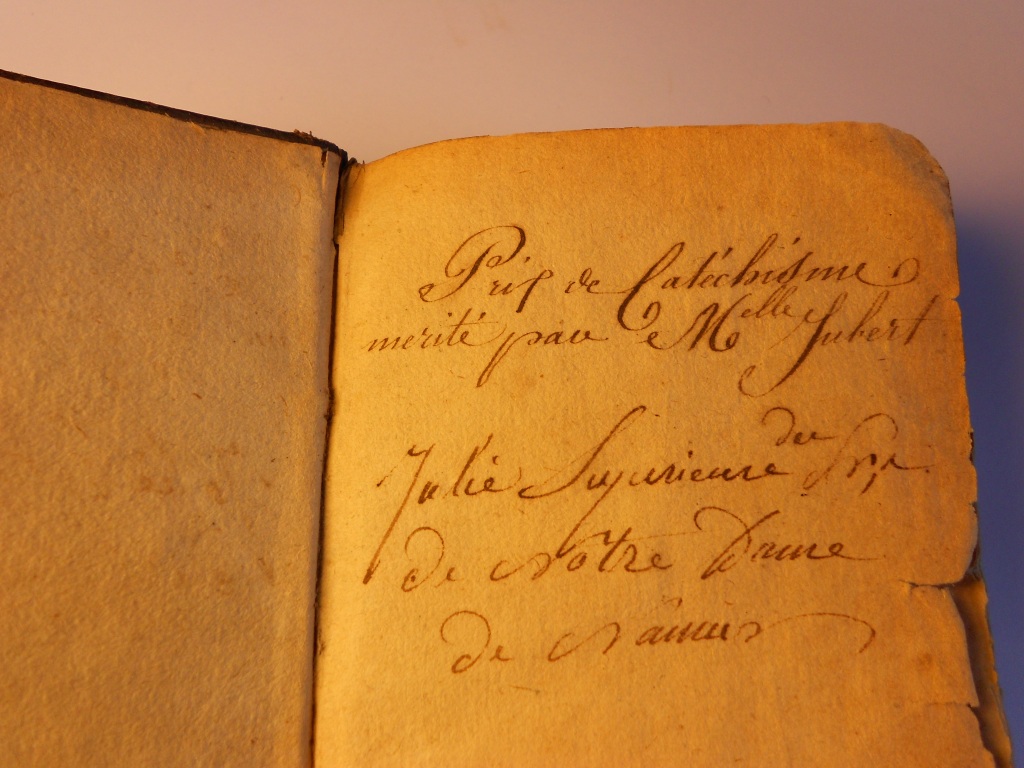

In order to keep a friendly competition among the students and combat absenteeism, the sisters distribute prizes to the most deserving (Julie Billiart, Letter 347, August 18, 1814.) In the Heritage Center, there are preserved, in addition, some books given as prizes to students and that bear the signature of Mère Julie.

Conclusion

Who would have thought that Julie Billiart, humble country girl without a great deal of education, would begin one of the most fruitful teaching congregations of the 19th century? As Sr. Mary Linscott highlights it: “Julie was an educator, not in theory but in practice.” Julie, who had probably no familiarity with the pedagogical writings of the time, is nonetheless going to show herself to be a great pedagogue. Her letters in which her educational outline is delineated reveal to us a person with a keen sense of humor and a limitless patience, always in a good mood. Julie hid neither responsibilities nor difficulties of such a mission. “ Let us bless the good God for sending us children! Do not forget, your responsibility before the good God grows with the number of children. The formation of young hearts in accordance with religion is not a small task. How difficult it is to form them well in the times in which we live!” (Julie, Letter 163, December 1, 1810) These letters are full of encouraging words that inspire the sisters in their work: ”We should like to see more abundant fruit; that would be very desirable but we live in a century which is not favorable. We must also pray for our dear children so that the good God may cause the holy seed to bear fruit in their young hearts. At their age we were no better than they are.” (Julie, Letter 204, April 11, 1812)

Text: Marie Felten, General Archivist of the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur and Sr. Christiane Houet, Coordinator of the Heritage Center of the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur

English translation: Sr. Jo Ann Recker

Bibliography

- All the documents reproduced in this text are preserved in the General Archives of the Sisters of Notre Dame in Namur (archives.generales@sndden.org).

- Marie Halcant, The Pedagogical Ideas of Blessed Mother Julie Billiart, Paris, 1930.

Who is Marie Halcant, author of The Pedagogical Ideas of Blessed Mother Julie Billiart (1930)?

Sister Marie Chantal (Elise Canivez, 1873-1934) is hidden under this pseudonym. In 1918, the Superior General asks her to collect in the letters, the writings, and the recollections of Mère Julie, the notes relative to the teaching and education of youth. This study was projected for a series of pamphlets entitled “Pedagogical Ideas of…” whose purpose was to honor “the founders of religious teaching Orders who had received from God gifted insights in order to achieve the aim of their Institutes.”

Sr. Marie Chantal establishes in the elementary classes of the schools of the Sisters of Notre Dame new procedures for instruction according to the “Montessori system.” Thanks to her, a renewal movement in “infant schools” arose everywhere in Belgium. Her exceptional work attracts the praise of eminent teachers of pedagogical studies and reaching into France and Switzerland. The expertise of Sr. Marie Chantal was unique in the early childhood domain where she was an initiator and a pioneer.

- Sr. Marie-Thérèse Béget, The Pedagogical Ideas of Julie Billiart, no date

- Cécile DUPONT, The Salvation of Souls by means of the Development of Feminine Education: The Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur, Educational Entrepreneurs (1804-1842), UCL, Louvain-la-Neuve, June, 2014

- Sr. Mary Linscott, To Heaven on Foot, 1969

Mother Aloysie, 6th Superior General (1875-1888)

Mother Aloysie, 6th Superior General (1875-1888) Monsignor Gravez, Bishop of Namur (1867-1883)

Monsignor Gravez, Bishop of Namur (1867-1883) Letter of Monsignor Gravez, Bishop of Namur, which accepts the request of Mother Aloysie with respect to the introduction of the causes of Julie and Françoise.

Letter of Monsignor Gravez, Bishop of Namur, which accepts the request of Mother Aloysie with respect to the introduction of the causes of Julie and Françoise. Note of invitation to the diocesan process

Note of invitation to the diocesan process Three large related volumes with all the letters of postulation for the purpose of the Introduction of Julie’s cause, General Archives of the Congregation, Namur.

Three large related volumes with all the letters of postulation for the purpose of the Introduction of Julie’s cause, General Archives of the Congregation, Namur. Cabinet with all the official documents related to Julie Billiart’s cause, General Archives of the Congregation, Namur.

Cabinet with all the official documents related to Julie Billiart’s cause, General Archives of the Congregation, Namur. Letter of postulation to introduce Julie’s cause signed by the Queen of the Belgians, Marie-Henriette (wife of King Leopold II), 1888.

Letter of postulation to introduce Julie’s cause signed by the Queen of the Belgians, Marie-Henriette (wife of King Leopold II), 1888.

Testimony of Sister Marie Adele Claus deposed at Clapham (Great Britain), July 15 1882, for the purpose of Julie’s beatification.

Testimony of Sister Marie Adele Claus deposed at Clapham (Great Britain), July 15 1882, for the purpose of Julie’s beatification. Decree of introduction of Julie’s cause, 1889. Julie becomes Venerable.

Decree of introduction of Julie’s cause, 1889. Julie becomes Venerable.

Shrine of Saint Julie exposed in the Heritage Center at Namur. To know more:

Shrine of Saint Julie exposed in the Heritage Center at Namur. To know more:  Pope Pius X, Cardinal Ferrata (Protector of the Institute in Rome). Monsignor Heylen (Bishop of Namur) and Mother Aimée de Jésus with their crest.

Pope Pius X, Cardinal Ferrata (Protector of the Institute in Rome). Monsignor Heylen (Bishop of Namur) and Mother Aimée de Jésus with their crest. Origin and meaning of the crest of the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur.

Origin and meaning of the crest of the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur. Poster of the celebrations in Namur for the beatification of Julie, May 17-21, 1906.

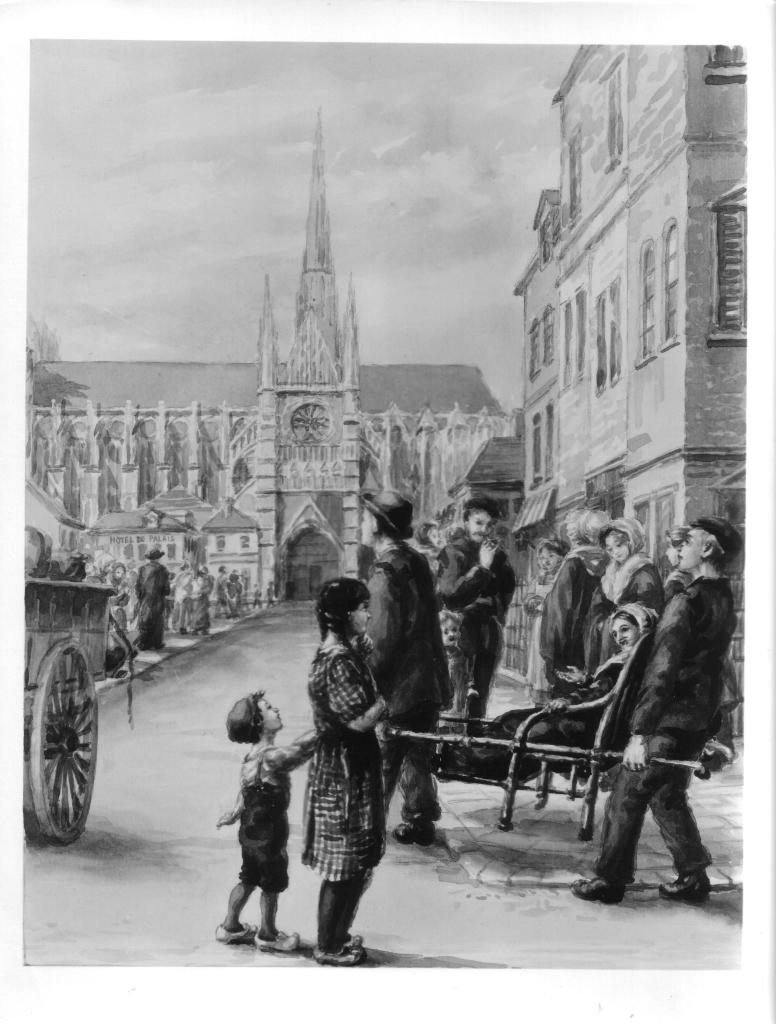

Poster of the celebrations in Namur for the beatification of Julie, May 17-21, 1906. Picture of the celebrations in Namur, 1906.

Picture of the celebrations in Namur, 1906.

Reverend Ugo Märton, O. Praem., Postulator of the Cause, thanks Pope Paul VI for Julie’s canonization.

Reverend Ugo Märton, O. Praem., Postulator of the Cause, thanks Pope Paul VI for Julie’s canonization. Canonization in Rome by Pope Paul VI.

Canonization in Rome by Pope Paul VI. Official decree (in parchment with illuminations) signed by Pope Paul VI, June 22, 1969. Julie Billiart becomes a saint.

Official decree (in parchment with illuminations) signed by Pope Paul VI, June 22, 1969. Julie Billiart becomes a saint. Louis Waëlens miraculously healed by the venerable Julie in 1886.

Louis Waëlens miraculously healed by the venerable Julie in 1886. Decoration of St. Peter’s Basilica, Rome, May 13, 1906

Decoration of St. Peter’s Basilica, Rome, May 13, 1906 Mr. Otacilio Ribeiro (miraculous cure) and his daughter, Julie.

Mr. Otacilio Ribeiro (miraculous cure) and his daughter, Julie.  Positio Super Miraculis listing the two miracles of the canonization, 1968.

Positio Super Miraculis listing the two miracles of the canonization, 1968. Banner made by Missori en 1968 for the canonization of Saint Julie. On can see Saint Julie with a Sister of Notre Dame de Namur and two “cousins” (a Sister of Notre Dame of Amersfoort and a Sister of Notre Dame of Coesfeld who claim the same spirit and follow the same rule but without juridical ties with the Congregation of the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur), surrounded by children from all the nations.

Banner made by Missori en 1968 for the canonization of Saint Julie. On can see Saint Julie with a Sister of Notre Dame de Namur and two “cousins” (a Sister of Notre Dame of Amersfoort and a Sister of Notre Dame of Coesfeld who claim the same spirit and follow the same rule but without juridical ties with the Congregation of the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur), surrounded by children from all the nations.

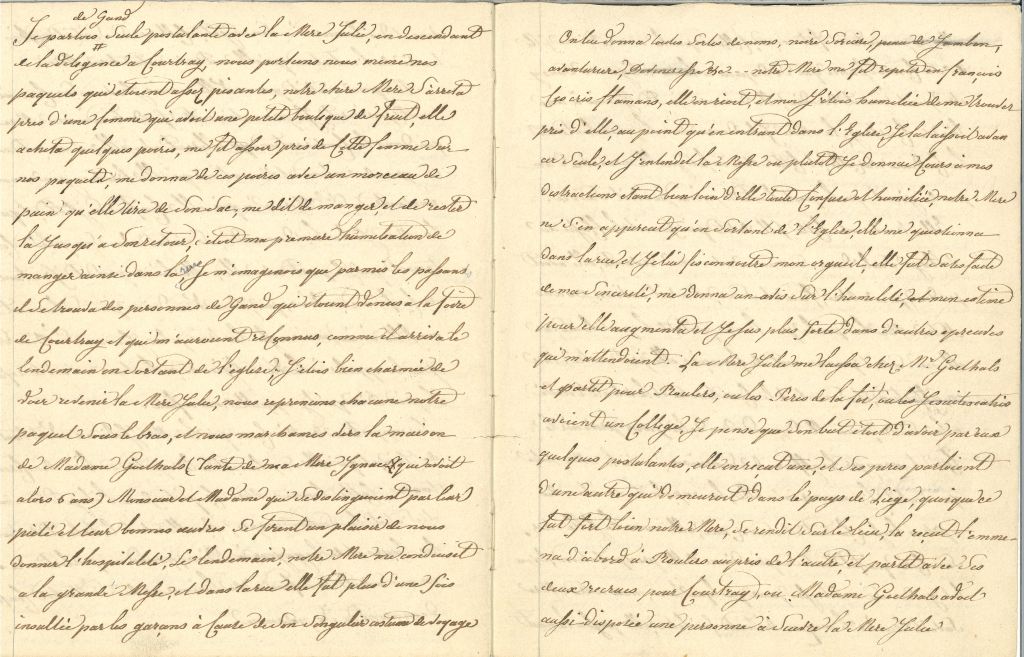

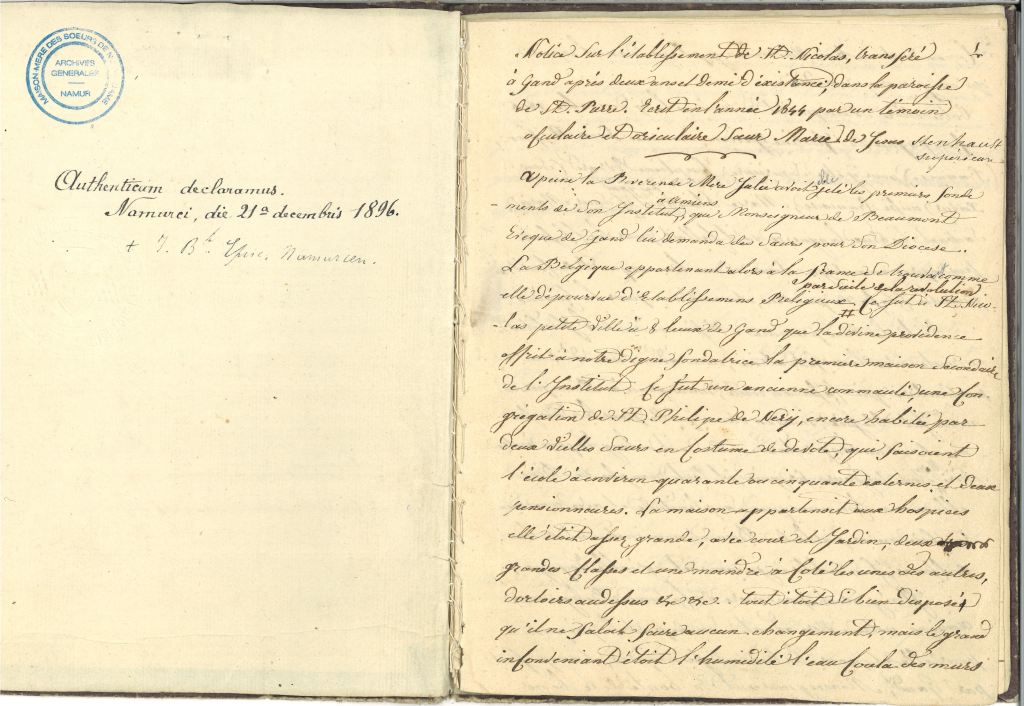

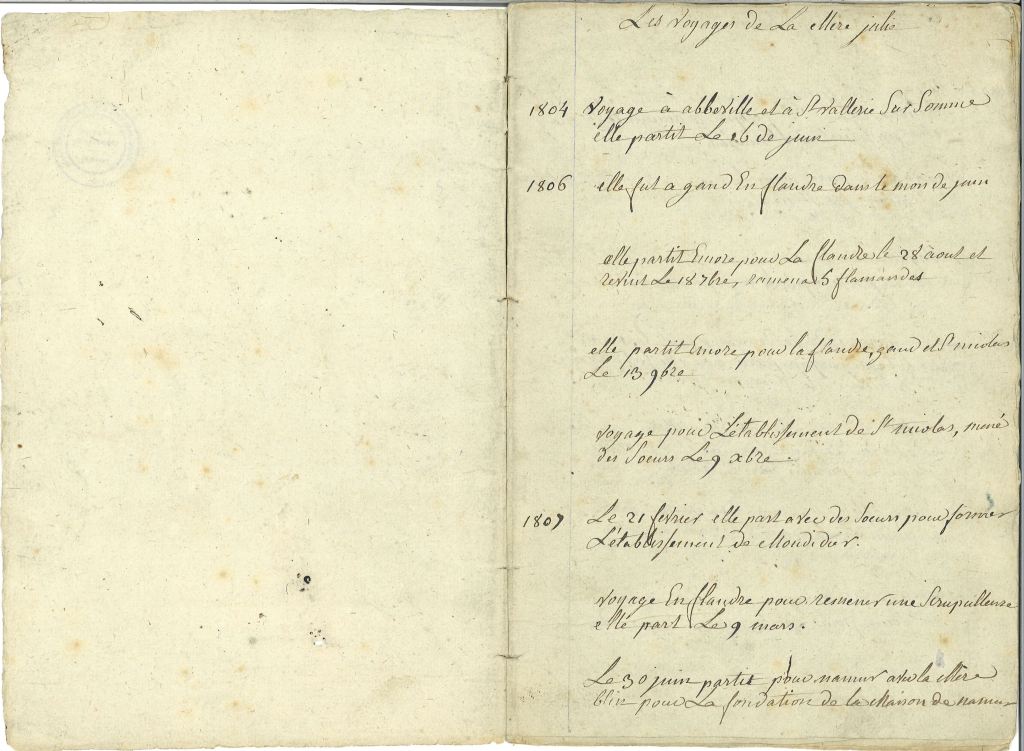

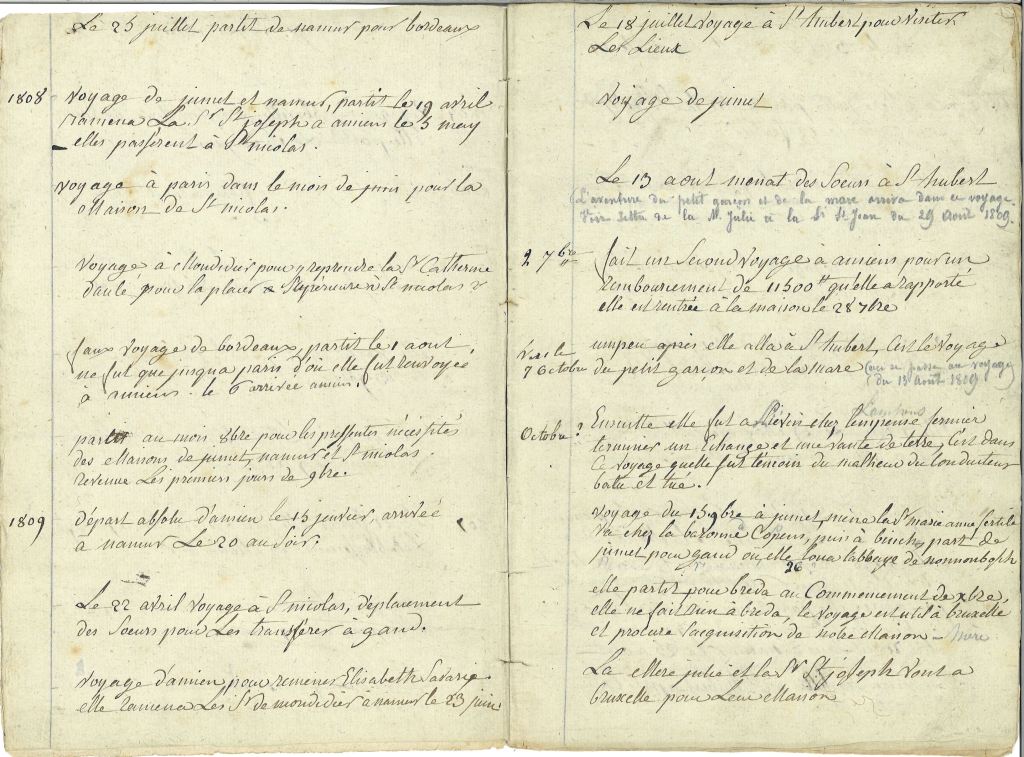

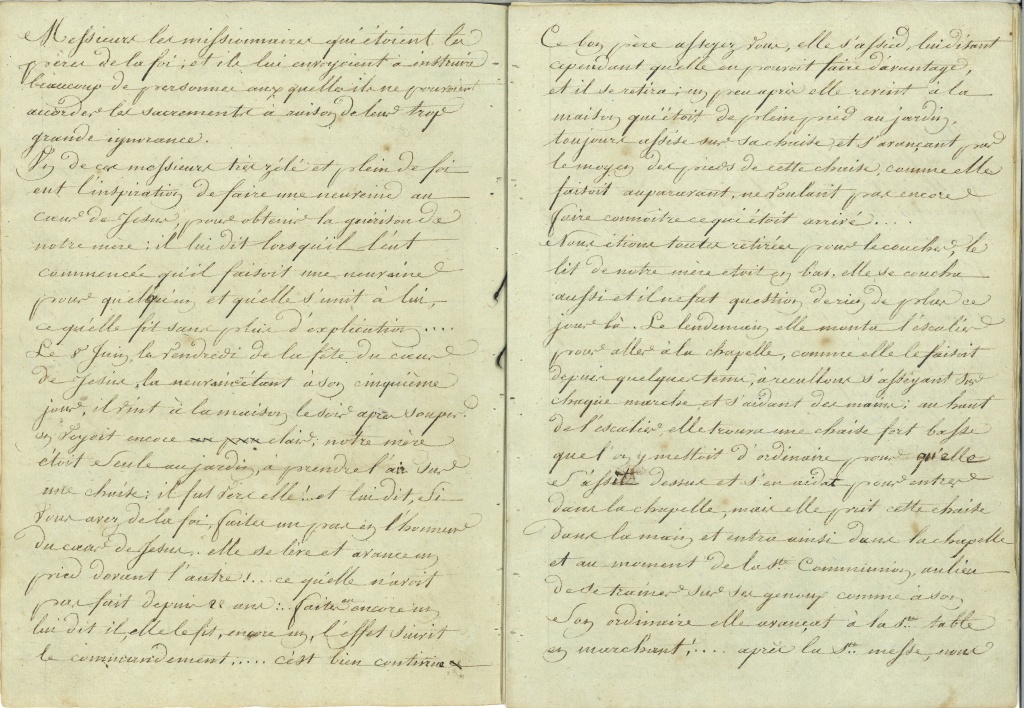

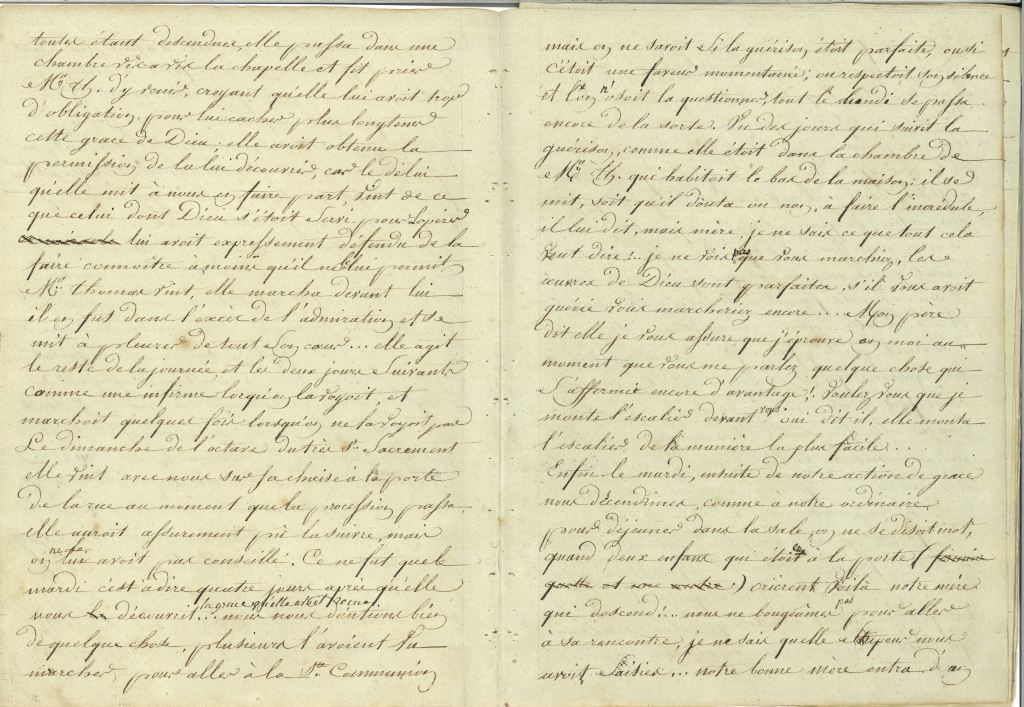

click to enlarge and to read the document

click to enlarge and to read the document click to enlarge and read the document

click to enlarge and read the document click to enlarge and read the document

click to enlarge and read the document click to enlarge and read the document

click to enlarge and read the document

Chateau of Gournay-sur-Aronde

Chateau of Gournay-sur-Aronde Graffiti on the chateau of Gournay, side wall: souvenirs of the troops who were quartered there during the revolutionary period: “the second battalion of Haute Vienne will stick it to the aristocrats – 1792 The Nasion – 1794 Hemeri”

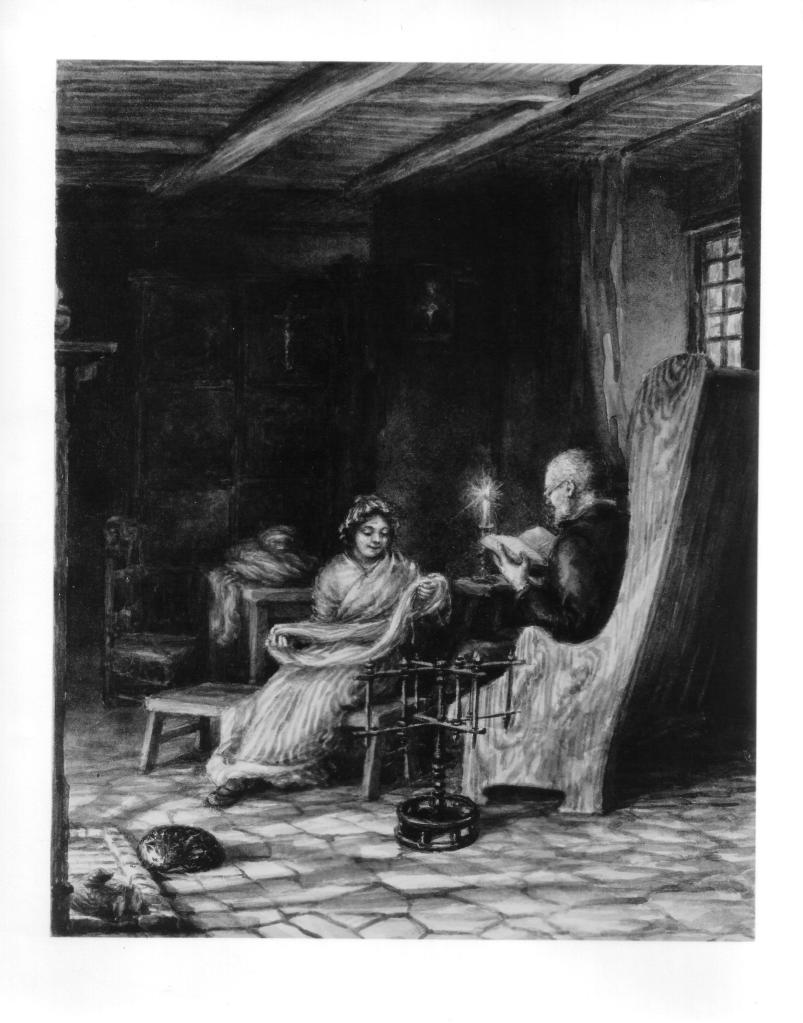

Graffiti on the chateau of Gournay, side wall: souvenirs of the troops who were quartered there during the revolutionary period: “the second battalion of Haute Vienne will stick it to the aristocrats – 1792 The Nasion – 1794 Hemeri” Julie transported in a hay cart with her niece.

Julie transported in a hay cart with her niece. click to enlarge and read the document

click to enlarge and read the document Click to enlarge and read

Click to enlarge and read